Silhouette

Introduction by Keiko Fukai

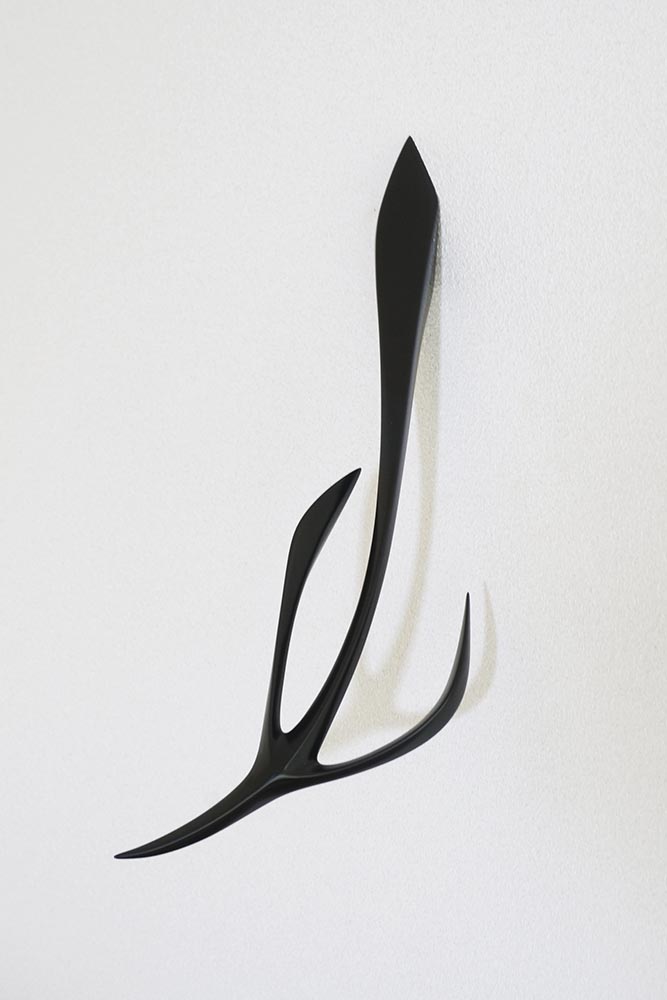

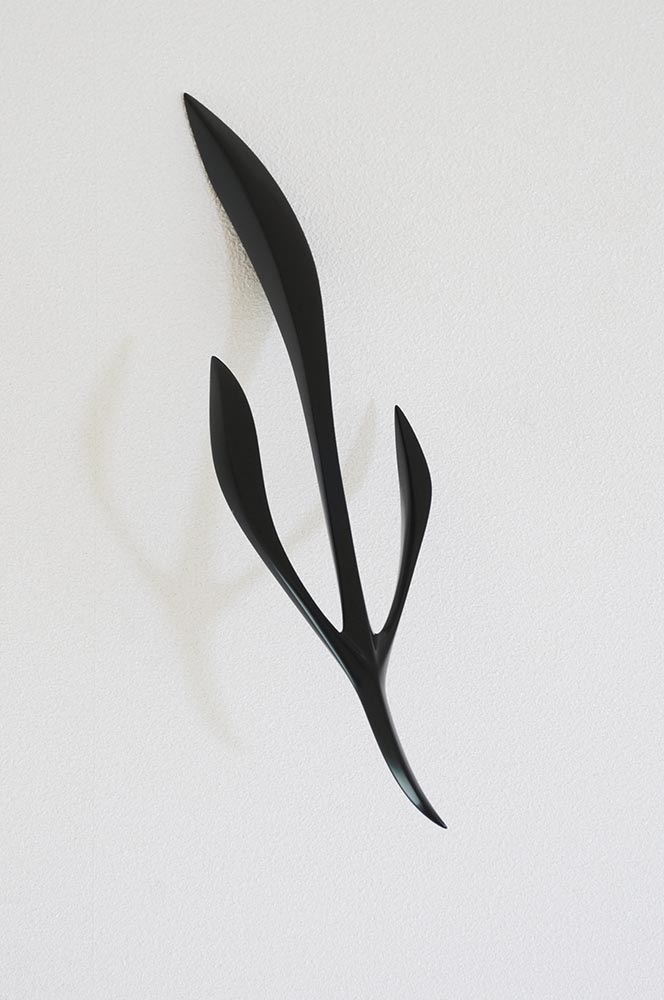

We are pleased to announce the online exhibition by a gifted young lacquer artist, MURATA Yoshihiko, who does mazing woodworking as well. His work relies heavily on the external play of light and shadow. His lyrical Silhouette series focus on anthropomorphic forms whose lines twist and turn, swell and fade, like capturing the motions of live activities in the nature. Simple, exquisite and profound, they share much in common with the brief poetic form, haiku.

I learned art and craft techniques in the Japanese city of Kanazawa in which the cultural traditions of Japan are still vividly alive today.

The reason I chose urushi (Japanese lacquer) as my medium is because I was interested in woodwork, and I wanted to create something with wood. However, there was no professor who could teach me woodworking in the urhshi course. Therefore I began to learn carving by myself.

Many of the forms of my works are made from solid kaede (maple) trees. I carve the shapes that I envision in my mind using a chisel or other small sharp knives. Kaede is a material that it is difficult to carve with a knife because of its hardness. However the reason I still want to work with kaede is because of its pliability. Yet because of the hardness, it is easy to break the kaeda when carving very thinly, but its pliability makes it as flexible as a bow. Based on my experiences with different woods, I believe that kaede is the best wood to express the smooth lines that I see in nature, and that inspires my work.

I always keep in mind that these lines should look beautiful from every angle and the lines should form a continuous flow on the surface to the borders or edges of the piece. As I work I have a clear image of the movement or undulations of a piece, and I strive for a beautiful harmony of the lines and the surface as a whole. This process seems to create the fine lines naturally.

Urushi, to me, possesses a mysterious depth as if it could swallow anything. At the same time the cool glossiness mercilessly does not show the effort and time I have spent. Moreover, it is a material that gives a feeling of deep, dark shadow.

Because of these feelings I had about urushi, when I was in college I began to create pieces that reflected this concept of dark shadows. Somehow this pitch-black glossiness of urushi connected the present to feelings and memories of my childhood that had remained in the back of my mind for years. At the time I realized this could feed my imagination with new ideas.

Then I had an opportunity to exhibit one of my pieces at school. When I put a spotlight on it, shadows that I had always imagined magically appeared on the piece. This experience gave me an unreal, transient feeling that was somewhere between a dream and being half awake. This important experience was the beginning of my pursuit of ancient Japanese aesthetics about the darkness of shadows and expressing those aesthetics in my own way.

Since I became interested in Japanese art and culture in college, I have seen many fine old works of Japanese art—Buddhist sculpture, Shinto art, black and white ink paintings, excavated ceramic figures, nishiki-e (brocade woodblock prints), tea ceremony utensils. Most of these things reminded me of the beauty of nature. Since ancient times Japanese people have believed that gods and spirits dwell in all of nature—trees, plants, stones, mountains, oceans, living creatures, the sun and the moon—and people believed strongly in these Gods. It seems to me this is why we Japanese continue to express the beauty of nature through our works of art.

This is the reason that I, also, use nature as the theme of my art. As I work I try to achieve the beauty and unique nuances of urushi, but at the same time I try to be modest and not express myself too much in my work. Instead I try to be satisfied when I have achieved something that is beautiful and also authentically Japanese. This is what drives my creativity.